/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/59059631/berendo_render_2_RGB.0.jpg)

For close to 100 years, Los Angeles has been a haven of architectural innovation and ingenuity. For even longer, it’s been home to countless residents living without a roof over their heads on a given night.

With homelessness in the city reaching epidemic levels, it’s fair to ask whether the many creative architects and builders who call LA home can contribute to growing efforts to alleviate the crisis.

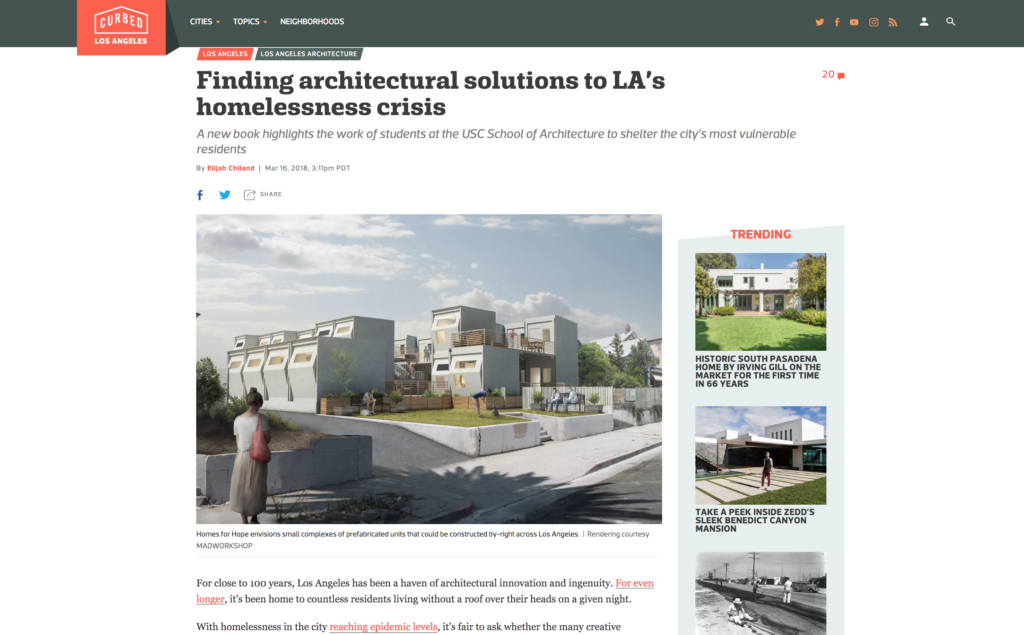

In 2016, the Martin Architecture and Design Workshop set out to answer that question, sponsoring a “Homeless Studio” at the USC School of Architecture for the fall semester. The program resulted in a new initiative called Homes for Hope, which plans to provide short-term housing to those awaiting placement in permanent supportive housing facilities tailored to serve the needs of homeless residents.

Homes for Hope has already partnered with Hope of the Valley Rescue Mission to design a concept for a small complex of prefabricated, easily reproducible units of housing. Working with the city, the organization plans to replicate the concept in other areas.

The formation of Homes for Hope and the work that students undertook to get the initiative off the ground is chronicled in a new book, Give Me Shelter, by Sofia Borges and R. Scott Mitchell. Curbed caught up with Borges —also an instructor at the USC Homeless Studio and director of MADWORKSHOP—to talk about the role of architecture and design in solving LA’s homelessness crisis.

In the book, you talk about working with students to see homelessness as an architectural typology. How is homelessness itself an architectural typology?

If you think about the idea of someone having to relocate multiple times per day every day for the indefinite future, it’s a crazy idea. Move everything you own? [Homeless residents] really are master builders. They’re versatile, they’re experimental, they are adaptive. And there is absolutely a vernacular to homelessness.

Even just the inventive ways that people use tarps—some of the students defined this as “tarpitechture.” There’s also the bicycle caravan, outfitting a bicycle to have different kinds of storage components. There’s a lot of ideas about mobility and flexibility that then informed the prototypes that students were developing.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10442403/IMG_8252_phBuddyBleckley.jpg)

What lessons can architecture students learn studying “tarpitecture” and homeless encampments?

I think there’s a couple things. One is you don’t have to be so precious about materiality to still produce really surprising and delightful spaces. And that there’s so many cheap—or free—solutions for building and repurposing. Now, students in this class look at the world in a totally different way. Like, that’s not garbage; that’s the top of my house. Basically it’s this idea that everything and everybody can have a second chance.

During the class, makeshift homes students had designed for homeless residents in Vernon were seized by the city. That must have been frustrating.

I get it, it’s not to code, but what was there right before? That’s to code? It’s frustrating because everyone can see that it helps. We put out those homes when it started to rain and people were dry and safe. They could lock their doors. It was such a huge improvement from how they were living. To have them seized, it wasn’t surprising, but it was like, “where’s the humanity in that?”

That’s why we’re working with the city [of Los Angeles] super closely and intentionally to make sure that the real solution is one that’s not only supportive but can last, because I don’t want to ever do another thing that just gets bulldozed.

In the book you write that this is a personal project for you because you lost your brother, who was homeless and struggling with mental illness when he died. How did that affect your career trajectory and approach to architecture?

It completely changed my career trajectory because it became a lot harder to justify doing things without social value. It became harder to justify being a designer, designing for those who have money—or talking about design for the upper class and completely neglecting the fact that there are humans out on the streets who don’t have shelter.

Doctors take an oath to help anybody, and I think as architects, we should do the same. We have a very specific skill set—to provide shelter. And shelter should be a basic human right. We have to be accountable to the fact that there’s a whole group of people that needs shelter, and we’re not providing it.

You call the shelter concept in the book a draft. Are you expecting revisions?

There’s no ego here; there’s no stake in this being the only way or the right way. This is the way the city will support and get behind—and hopefully be able to do—but if you have a better idea, go for it. Let’s just do something. We all just need to do something. There’s people out there in the rain and the cold, and we’re not doing anything.

I’m all for all the ideas, all the revisions. But I hope that it makes people want to act, because I can’t do it alone. Nobody can. We have to strengthen our ties as a community and decide that this isn’t an acceptable way to live with tens of thousands of people outside suffering.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.